This story first appeared in the Fraser Valley Current newsletter. Subscribe for free to get Fraser Valley news in your email every weekday morning.

With Abbotsford’s $3 billion plan to protect Sumas Prairie yet to receive the funding needed to allow it to proceed, experts are considering a range of alternatives, including a plan suggested by BC’s former Inspector of Dikes.

Neil Peters says a floodway that runs south of the former Sumas Lake bed, rather than north of it, has the potential to offer more protection for less money than the flood plan sketched out by the City of Abbotsford. The southern floodway concept would require significant study to determine its feasibility, Peters cautioned. But he said that its benefits are worth consideration as politicians and flood experts on both sides of the border try to find a solution to the threat posed by the Nooksack River.

The expert

Few people know more about the Nooksack River and the danger it poses to Sumas Prairie than Peters.

An engineer by trade, Peters sat on, and eventually co-chaired, the Nooksack International Task Force that was created in the 1990s to try to find a solution to the river’s cross-border flood threat. But that body was stymied by a lack of political support and funding, Peters said.

“We couldn't even get $25[,000], $50,000 to do a little bit more modeling,” Peters said. (Look for our interview with Peters about the past and future of flood management talks in a future edition of The Current. Subscribe here.)

As the province’s Inspector of Dikes for more than a decade, Peters regularly warned about the insufficiency of the Lower Mainland’s flood protections. He continued to raise the alarm about flood threats after he left the province.

His experience and history means that when Peters creates an eight-page draft proposal of a potential floodway alternative to a $3 billion scheme that has been unable to secure the necessary funding, it’s worth considering.

The Peters proposal

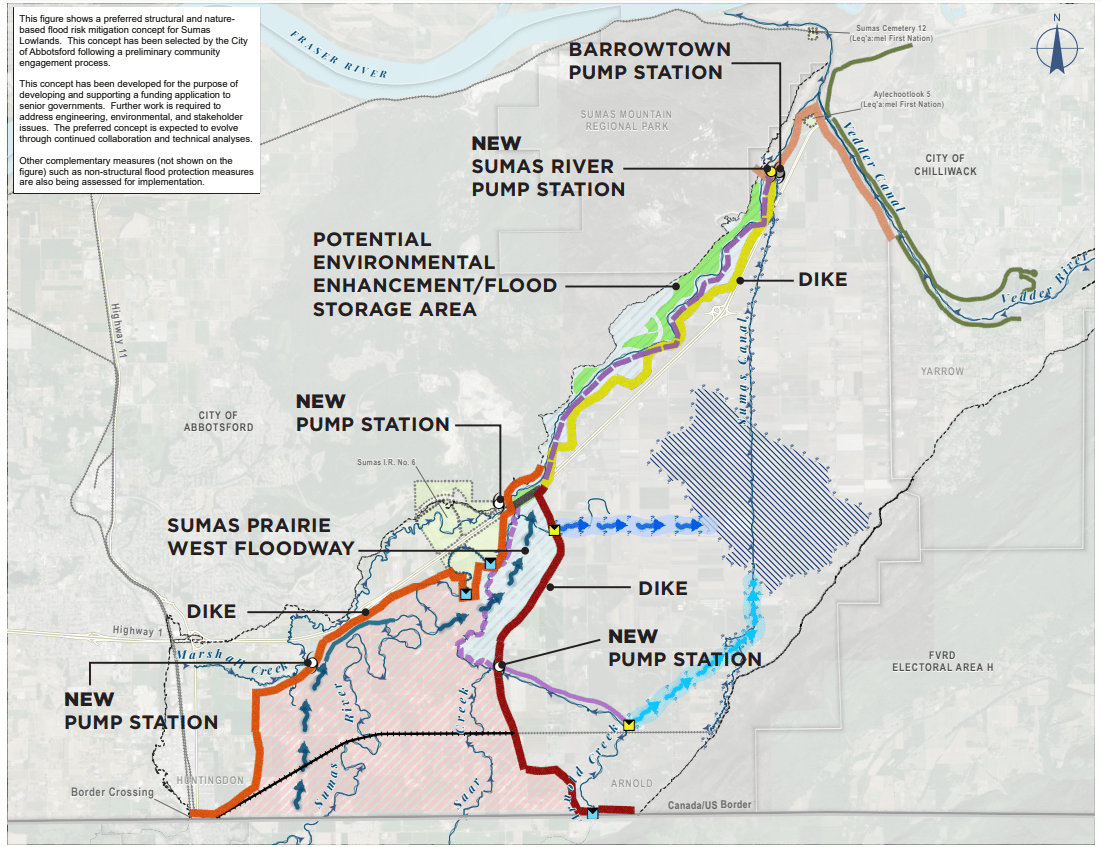

In 2023, after more than a year of study, the City of Abbotsford endorsed a comprehensive, and very expensive, plan to mitigate future flooding from the Nooksack River. That plan, which the city forwarded to the federal government as part of a funding application, was complex, but had a few key elements. Essentially, it proposed the construction of new dikes that would create a broad funnel that would route water across western Sumas Prairie, north of Highway 1 (and north of the former Sumas Lake bed), to a new Barrowtown pump station. That pump station could pump water up to the Fraser River when the Fraser was higher than the floodwaters—as was the case in 2021.

The concept would cost upwards of $3 billion. Around one-quarter of that cost—$870 million—would be used to build a pump station to help move water out of the prairie and into the Sumas River, from which it would travel to the Fraser. The concept would protect the Sumas Lake bottom but leave a considerable amount of land in the western part of Sumas Prairie vulnerable to flooding.

Abbotsford’s preferred flood management concept would route water along the base of Sumas Mountain, north of the Sumas Lake bed. It would also leave the western part of Sumas Prairie vulnerable to future flooding. 🗺 City of Abbotsford

Peters’ suggested concept is very different. (It’s not quite a proposal, since Peters himself acknowledges it may not end up being worth pursuing.)

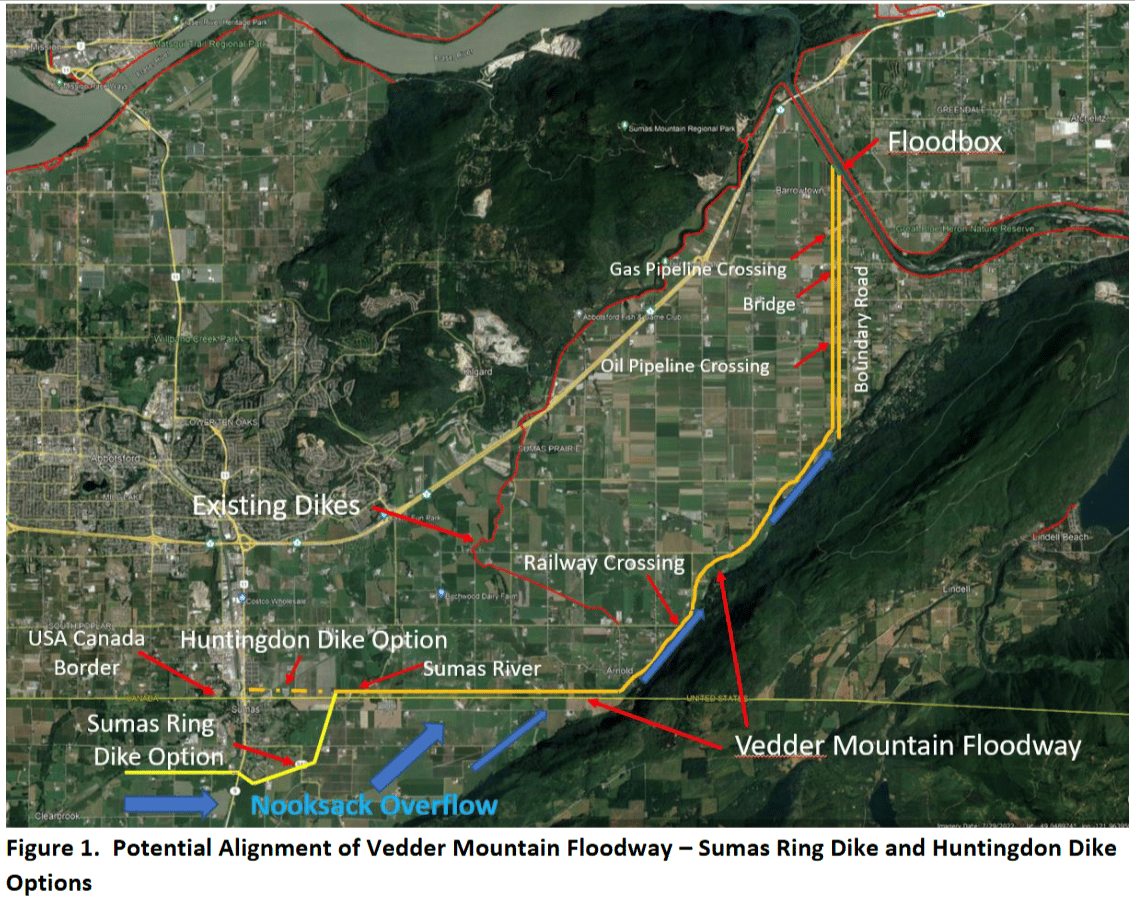

His idea would see the creation of a large dike along the US/Canada border that would channel water directly east toward the base of Vedder Mountain, rather than north to the base of Sumas Mountain. The dike would then swerve northeast, parallel to Vedder Mountain. That would create a new floodway between the dike and mountain’s base. At the Chilliwack/Abbotsford border, that floodway would turn directly north, with dikes on either side. It would channel water to the Vedder Canal, into which the water would flow via a large floodgate. From there the water would continue on its way toward the Fraser.

Neil Peters’ proposed concept would route water along the southeastern edge of Sumas Prairie toward the Vedder Canal. 🗺 Neil Peters

Peters sketched out three possible dike alignments to stop the water’s flow directly north into Canada. In one version, a dike could be built along the US/Canada border. That could cause water to backup in Sumas, Wash. But flooding of that community could be avoieded through the creation of a ring dike, a possibility already under consideration. With the water unable to flow directly north into Canada, the only downhill route left to it would be through the Vedder floodway.

Such a floodway, Peters said, could offer much better protection to farmers, property owners, and residents in the western portion of Sumas Prairie. Under the city’s plan, some of them would remain vulnerable to large overflows from the Nooksack. Floodgates along the Sumas River could allow that waterway to function as it does now, with water only routed south of the Sumas Lake bed only when the Nooksack breaches its banks.

In addition to offering better protections for landholders in the western Sumas Prairie, Peters suggested the plan could also end up being cheaper—and an easier sell to politicians—because it wouldn’t require a massive new pump station.

Abbotsford wants to build a $700 million pump station to replace a series of floodgates near the Barrowtown Pump Station. 📷 Tyler Olsen

The pump station question

In 2021, the Nooksack’s overflow that entered Sumas Prairie was unable to drain out of the area because the Fraser River was also running at abnormally high levels. Until water in the prairie rose above that of the Fraser, floodgates near Barrowtown Pump Station had to remain closed, leaving the prairie to fill up with water like a bathtub. Before that water could drain into the Fraser, it overtopped—then broke through—a key dike protecting the bed of Sumas Lake.

To avoid a repeat, Abbotsford has proposed the construction of a $700 million new pump station that could pump the Nooksack’s water up and out of the new floodway and into the Fraser.

Peters, though, says his concept could—theoretically—function without such a pump station. Instead, with no low-lying prairie for the water to collect in, gravity would be able to funnel the water directly into the Vedder. In 2021, the elevation difference between the border and the Vedder Canal was roughly four metres, Peters said. (All these calculations and assumptions, Peters cautioned, would need rigorous checking.)

Creating a more-confined, direct route between the US and the Vedder Canal and Fraser River should hypothetically allow gravity to drive the water toward the canal and the Fraser.

If the floodway was large enough—up to 200 metres wide between the dike and Vedder Mountain—Peters estimated that it could transport huge volumes of water to the canal. (Floodgates at the canal would also need to be huge. They would need to allow water to move from the floodway into the canal with minimal friction, but also be able to stop water from flowing into Sumas Prairie during normal times.)

Peters said the idea would also tie in well with flood protections being considered south of the border. A ring dike protecting the city of Sumas, Wash., could increase the elevation of the water entering the floodway and, thus, the “head” of the water flowing into the floodway. That would increase the ability of gravity to move the water from Washington into the Fraser River.

There’s one other major potential benefit and cost-saving: Peters’ concept, if feasible, could forestall the need to raise Highway 1 along Sumas Prairie. The widening of Highway 1 to Chilliwack has been promised by the provincial government, but the flooding of the route in 1990 and 2021 shows that it is highly vulnerable to a Nooksack flood all the way from the Whatcom Road interchange in Abbotsford to the Vedder Canal. The province has said plans to flood-proof the route lie at the heart of delays in expanding the highway to Whatcom Road, the site of some of the worst flooding.

Abbotsford’s $3 billion plan would route the Nooksack’s floodwaters beneath the highway at a bridge near the Cole Road exit. In 2021, the highway was closed for days to allow for a “tiger dam” to be erected at that bridge. Abbotsford’s concept would still require significant earthworks at the current bridge—and potentially raising the entire length of the highway across Sumas Prairie. Creating a floodway south of Sumas Lake bed to the Vedder canal would route the Nooksack’s floodwaters far away from Highway 1. The water would eventually need to pass underneath the Vedder Canal bridge, but that structure is scheduled for replacement in any event—and should already be high enough to not be significantly affected by a more robust Vedder Canal.

A ‘tiger dam’ was built across Highway 1 in 2021 to prevent future flooding into the Sumas Lake bed. The highway remains vulnerable to future floods. 📷 Ministry of Transportation

Questions

Peters said he has not encountered any previous discussion of the Vedder Mountain floodway concept. It wasn’t studied while he was part of the international task force, he said. Shortly before the 2021 flood, consultants hired by Abbotsford explored a range of possibilities—including potentially drilling through Sumas Mountain—but not, seemingly, the Vedder Mountain concept.

“It’s funny,” he told The Current recently. “When I started thinking about this, I couldn’t find anybody who’d actually proposed this before… I think the reason why this hasn’t come up before is because it was just too massive an idea.”

By a “massive” idea, Peters means it comes with a huge price tag. And yet, post-2021, it could be relatively cheap.

“The only reason I started thinking about it now is because the pump station cost was so huge,” he said. “Does it make sense to have a piece of equipment sitting there for a couple decades without running and then all of a sudden have to perform exactly as designed, with all that power available at any moment? I don’t know. It seems challenging.”

Peters, though, made clear in both his report and an email to The Current that the concept is just that: an untested concept needing further study.

Nearly one-quarter of his eight-page report is spent listing various tasks needed to determine if the concept is worth pursuing or is flawed. Peters, who now works part-time for a hydrological engineering company, ball-parked the cost for answering the questions in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. He made clear in his report that he’s not looking for any work out of his project.

Environmental impact studies, floodway modelling, and a variety of other work would need to be done to probe every potential flaw in a plan that, even if it would be cheaper than Abbotsford’s current preferred flood scheme, would still likely cost more than a billion dollars. Experts would also, obviously, need to start to put a price tag on the concept to determine if there would actually be any potential overall cost savings. Part of that would be determining how much property might need to be acquired along the length of the floodway.

Some of the challenges seem to have potential solutions. For instance, the elevation of potential floodwaters in the Vedder Canal might rise above 2021

levels during a future storm event and compromise the gravity-flow of the floodway meant to capture the Nooksack’s overflow. If the Chilliwack and Nooksack rivers were to experience large-scale flooding at the same time, that could impact on the Vedder Canal’s level and subsequent gravity flow. (The Chilliwack River saw moderate, but not major, flooding in 2021.) Peters suggested that challenge could be alleviated by removing sediment from the canal.

The potential for erosion along Vedder Mountain could be ameliorated by the gradual gradient of the water moving along the floodway and protections of its edges.

And inevitably, further investigation can bring up issues that haven’t yet been identified.

Sumas Lake once filled the broad valley between Vedder and Sumas mountains. 📷 Tyler Olsen

The future

Peters first sent his concept document to the City of Abbotsford’s engineering department in March 2023, thinking it may be of interest. He heard nothing back, but said he wasn’t surprised or upset.

Peters’ concept would have been received at an awkward time, and the city’s silence was perhaps understandable: Abbotsford had committed to its preferred option and was hoping the federal government would do the same. It wasn’t about to waver from its plan to explore an eight-page concept that hadn’t been investigated or tested. And Peters himself didn’t want to publicize his alternative concept, lest it be seen as an attempt to derail Abbotsford’s funding request.

“I’m not really promoting it, I’m just ‘maybe here’s another idea,’” he said. “I didn’t want to put it out in the public without Abbotsford having control of the situation, now that they’ve kind of been turned down for money it seems that everything’s on the table again, so I didn’t think there’d be any harm in letting the idea float around a bit now.”

Indeed, Abbotsford’s $3 billion plan is now in limbo, though the city insists it still wants to pursue the idea.

After the 2021 flood, Abbotsford city staff spent much of 2022 working with consultants on exploring potential new layouts for flood protections that could avoid a repeat of the disaster. Those layouts followed a pre-flood study from 2020 that had considered improvements to flood protections north of the Sumas lakebed. By June of 2022, following consultation with residents, the city combined four potential protection schemes into a single “preferred option.” The $3 billion cost, though, was so large that there was no way Abbotsford could pay for it on its own.

Instead, Abbotsford took its preferred option to the provincial and federal governments, asking them to pick up the cost and emphasizing Sumas Prairie’s importance as a national transportation corridor and food source. In July 2023, the city submitted a 57-page application for funding to Ottawa and hoped for the best.

This summer, however, Abbotsford was told that the federal government had rejected an application for $1.8 billion, which would have been used to fund the most urgent parts of its Sumas Prairie Plan. The response prompted bewilderment from city officials, who said they didn’t have a good reason why their application was denied.

The city still says it is seeking funding for the most-urgent components of that plan and has yet to back away from the application. The Fraser Valley’s Conservative members of Parliament released a statement saying they were “shocked” that Abbotsford’s application for funding was denied.

So for the moment, the future of flood protection on Sumas Prairie remains up in the air. It’s possible that Abbotsford is holding out hope that next year’s federal election will bring a government willing to ante up the billions needed for its current flood plans.

But - and now seem to also be considering other options. (That initiative, notably, includes representatives from Washington State and the Province of BC, but not the federal US or Canadian governments.)

And although Peters has been largely left out of the conversation, his concept hasn’t been thrown in the trash. Now that the city’s Plan A is in limbo, Peters’s concept may get a closer second look

In July, a City of Abbotsford spokesperson told The Current that Peters’ proposal is “currently one of the options being evaluated” by a team of technical experts convened as part of the Nooksack and Sumas Watershed Transboundary Flood Initiative.

With Abbotsford’s desired Sumas Prairie flood protections coming with such a high cost, it’s also easy to imagine a new government suggesting that more be done to explore whether one of BC’s foremost flood experts could save them hundreds of millions of dollars.

This story first appeared in the Fraser Valley Current newsletter. Subscribe for free to get Fraser Valley news in your email every weekday morning.

If you read and appreciate our stories, we need you to become a paying member to help us keep producing great journalism.

Our readers' support means tens of thousands of locals in the Fraser Valley can continue getting local news, and in-depth, award-winning reporting. We can't do it without you. Whether you give monthly or annually, your help will power our local reporting for years to come. With enough support, we’ll be able to hire more journalists and produce even more great stories about your community.

But we aren’t there yet. Support us for as low at $2 per week, and rest assured you’re doing your part to help inform your community.

- Tyler, Joti, and Grace.