📸 Shelanne Justice Photography

Meghan Fandrich is sitting at a coffee shop, talking about how she’s not a poet.

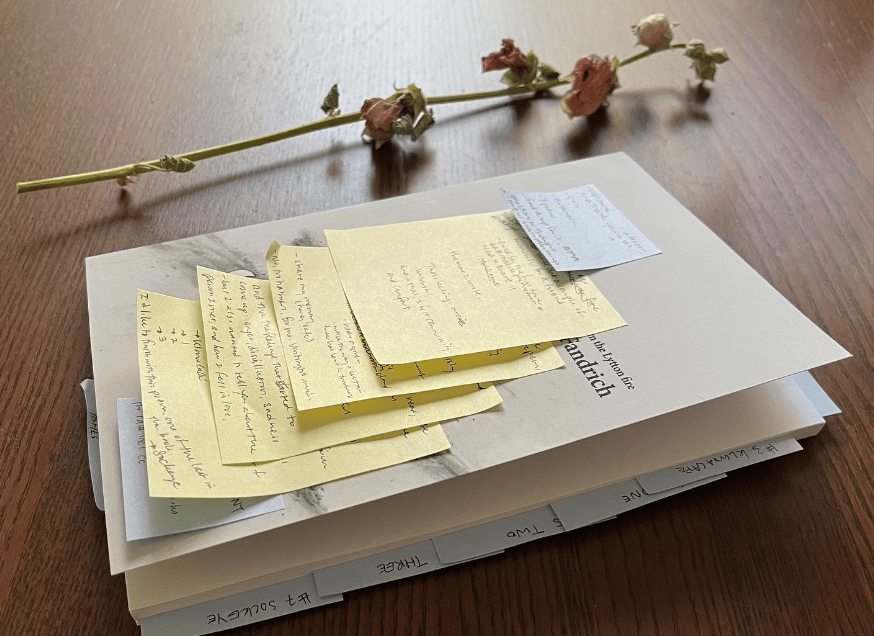

In front of her sits a book of poems, with her name on the cover and praise from one of the country’s most decorated poets on the back. Fandrich is a poet. But her reluctance to proclaim herself one is understandable, given how it all came about.

A year after she fled Lytton and the café she had built into a community institution, Fandrich started writing her first poems. She mined her emotions, dumped them onto a blank page, then—feeling a new compulsion to share—sent them forth into the world. As she did so, she felt the burden of the fire lift. And in the year since, she has started to see the possibility of a new future materialize: one built not around coffee and toques, but around a new career in, of all things, poetry.

Fandrich grew up in Lytton—her father built Kumsheen Rafting Resort into Lytton’s largest business. And in 2014, after years of travelling around the globe, Fandrich returned to her hometown and started Klowa Art Café.

The café began as a place where Fandrich could sell her knitting. And by 2021, after years of plowing all the profits back into the business she had built Klowa into a place with a formidable reputation for tremendous coffee and a clientele that stretched far beyond the confines of Lytton.

But on June 30, 2021, on a blazing hot June afternoon, a fellow Lytton resident burst into her café and told her she had to leave immediately.

Fandrich’s home on a hill immediately above the Lytton townsite was spared through a fortuitous combination of weather, community vigilance, and firefighting. But Klowa was destroyed, as was the community Fandrich has grown up in.

The day the fire swept through town left Fandrich—and many others—with severe trauma. The two years since have brought frustration about the lack of rebuilding and stress from new fires.

The book Fandrich is holding and the poems within it are about that moment and those that followed. They’re about Lytton, the fire, the emotional wreckage it and other events from that horrible year left behyind. They’re also about what it’s like to live in a world that has changed irrevocably.

But what the poems are about might matter less than what the poems did.

📷 Meghan Fandrich

Beyond survival

In the year following the fire, Fandrich talked about the destruction of Lytton, advocated for its rebuilding, and started therapy.

But one day last August, while trying to raise a five-year-old girl in a town that no longer existed, she sat down and started writing. Her goal was simple: jot down a memory for a friend. When she was done, she found had written a poem.

Fandrich had a minor in English literature and had journaled throughout her life, so she wasn’t unfamiliar with writing and poetry. But she wasn’t exactly in the habit of writing poetry. She was surprised both by the form and by how it made her feel.

The act of writing was cathartic, so she kept writing, and the words kept pouring out of her.

“I felt like [the writing] was just unearthing things and externalizing them and getting it out so they weren’t haunting me anymore,” Fandrich told me, more than a year later. “It felt like, until that point, I was focused on survival.”

The intense trauma—that focus on just getting through each day—didn’t disappear. Fandrich was still, as she put it, “a single parent in a burned up town.” And ever since the fire, there has been lots to deal with. An atmospheric river that severed vital highway connections. A historically snowy winter. A rebuilding that seemed forever delayed. And the memory of fleeing for one’s life.

Fandrich felt like those memories, those experiences, were embedded in her body. Writing and crying seemed to help.

“I felt that by actually writing it out, it removed them from my body.”

But she wasn’t just writing poetry and sticking it in a drawer. She also felt the “intense need” to share it.

“I would write a poem and immediately send it to a friend, or even an acquaintance, or someone would come over for tea and I’d be like ‘Read this!’”

Fandrich speaks about poetry the way some talk about counselling and therapy. She found that sharing her feelings could set them free, in a way.

“Now, this awful haunting thing doesn’t belong to me anymore,” she said. “Now it’s something that’s out there and has been acknowledged and is no longer so awful.”

Her poems were raw. They were about fleeing the fire. About the hometown she watched burning as she fled. About trying to recover from a moment of terror and loss. Sometimes they were also about healing and falling in love.

Many people experienced terror and loss that horrible year. Homes at Monte Lake and the Okanagan Indian Band burned. Communities in Merritt and Abbotsford and Chilliwack were flooded a few months later. All across the province, hundreds, if not thousands, were trying to put their lives back together and dealing with the mental legacy of their particular disaster.

And just because others are going through similar things doesn’t necessarily help, Fandrich said.

“This is a collective trauma, but this is individual suffering,” she said. “You are stuck in your experience and the only way you can get out of that individual isolation is to share.”

Poetry and prose

Fandric tried to write about her experience in simple prose. But it didn’t come out right.

There was, she said, “too much cushion and too much flower.” Prose, ironically, was too fancy.

Poetry has a reputation for density, metaphor and abstractness. But Fandrich’s poems were, at their core, raw expressions of emotion. They’re not overwrought or overly complicated or bogged down by metaphor. They’re simple and plain and clear.

“I wrote poetry not in a way that’s like hiding behind some complicated use of language. I’m trying to just expose the most pure and raw and vulnerable thing I can.”

The simple language, in other words, was a choice.

“I was also writing these poems with my community in mind. Hoping others would read this—[others] who aren’t poetry readers.”

📷 Meghan Fandrich

The joy of editing

As Fandrich tells it, the poems—their subject, emotion, and structure—flowed onto the page more or less spontaneously and unbidden. Then the real fun began: editing.

Fandrich says editing pieces of writing has always been her “guilty pleasure”

“To apply editing to poetry for the first time, I loved it,” she said. “It was so cool.”

Fandrich tinkered, looking at a poem and considering not just the word choice, but their placement on the page.

She would ask: “What if I move this one over by an eighth of an inch? What happens to the font?”

She spent hours, days, and months like that, polishing and polishing and polishing. In doing so, she was also editing her future into something very different.

Impostor

Fandrich started writing last August, a little more than a year after the fire burned her town. She was still living in Lytton, raising her daughter, and watching as rebuilding remained a goal, rather than a reality. Poetry gave her an outlet. Editing gave her joy. It also gave her a little bit of a complex.

Fandrich was sharing her poetry, and finding that process helpful and gratifying.

But she still wasn’t quite sure whether it was actually any good, even as she began to realize that the poems could be collected into a book; a coherent collection of writing about the arc of one person’s emotional trauma, as she puts it.

“I went through intense impostor syndrome,” she said. “I was sharing it with people and they were having these emotional reactions, but the next morning, I’d wake up and say ‘Oh they were just faking it so I didn’t feel bad.’

“I remember one day waking up and I could feel it with the tips of my toes that it was complete garbage. And this was after four months of getting really loving feedback.”

Eventually, Fandrich realized it almost didn’t matter. If her readers were having honest emotional reactions, as they seemed to be, then that would be good enough.

“The more I shared it…and people were really responding to it, I was like, ‘OK. It has emotional value. Even if it has no literary value, it has emotional value and I did something right.”

But it kind of did still matter, and Fandrich continued to doubt herself.

So she began to share her work not just with fellow readers and friends and community members, but with actual poetry editors and publishers. (And also Elizabeth May.) An American poetry editor applauded her work, allowing Fandrich to sleep a little easier. A publisher said she wanted to publish the poems in a book. May agreed to write an enthusiastic endorsement for the book’s back jacket. May’s husband, John, meanwhile forwarded them to his friend, Lorna Crozier—a legendary Canadian poet who not only gave her stamp of approval, but also delivered a blurb for the back of the book.

Getting the emailed contract from her book publisher, Fandrich said, was a landmark not just in her post-fire recovery, but her life as a whole.

“I started dancing in the kitchen and started feeling real joy for one of the first times since the fire. It felt validating for my entire life. Even as a kid, I would write lists of what I wanted to do when I grew up, and one was ‘Write something worth reading.’

📷 Shelanne Justice Photography

A life beyond Klowa

Since she danced in her kitchen, things have moved fast—deliberately so. The formal editing process was a relative breeze, given all the work Fandrich had previously done. Burning Sage, as it is called, was born.

Fandrich’s friend designed the book’s stark jacket, and seeing that cover was another highlight. Actually getting the book in her hands, weirdly, was surprisingly less so—maybe because by that point she found herself in the thick of planning a book tour throughout the Interior.

As that tour neared, there was another major challenge: the return of fire to the canyon.

August was tough. A new fire sprung out of the Nahatlach Valley and raced north, in the direction of Lytton. At the same time, the flames of another fire could be seen north of town, and the village was placed on evacuation alert.

Before the fires Fandrich had felt as good as she had in years, if not decades. The fire—and the smoke that followed even after the advance of the flames slowed—brought the trauma all back.

“I was up all night looking through my daughter’s bedroom window to see if the flames were coming,” she said. “In the end, it was so far away. But we had no idea.”

Only when the smoke lifted—long after the actual fire threat stabilized—could Fandrich breathe again.

Fandrich is still paying two mortgages on her café. She had insurance, but the payout was capped at $250,000 and won’t be nearly enough to actually rebuild half of what was lost. If she doesn’t rebuild, she’ll only get a fraction of that payout sum.

“Every single day, I’m like, ‘Shit, how am I going to do today’s payments.”

But if Fandrich doesn’t expect to be able to rebuild Klowa, she also doesn’t really want to.

This month and next, she will tour the province with her book of poems, talking to both new faces and hundreds of supporters, friends, and family.

“Community is a lot greater than just the people in a town with you,” she said. “For me, that was a big lesson: to actually realize I’m not alone and isolated because there is this community around me.”

Beyond that, poetry has given her a new plan—and a new job, with her publisher offering work editing the poems of others. A new post-Klowa career beckons.

“I tried to settle down and be this mother, wife, business owner—all of these things. Then whatever wasn't already gone with divorce and whatever else, burned up in the fire.

“Now I can actually travel again with my kid who's never lived in other places and do editing, which I love. I don't love payroll, and bookkeeping, and managing employees and ordering—all of the stuff that I was doing. But I really love editing, and especially poetry.”

Fandrich doesn’t know whether she will write more poems. She doesn’t know what the future holds. But she is a poet.

Burning Sage is available online from Caitlin Press, local booksellers, Chapters, and Amazon.

Fandrich will be hosting a reading and book signing Oct. 16 from 3 to 4pm at Oldhand Coffee in Abbotsford.

If you read and appreciate our stories, we need you to become a paying member to help us keep producing great journalism.

Our readers' support means tens of thousands of locals in the Fraser Valley can continue getting local news, and in-depth, award-winning reporting. We can't do it without you. Whether you give monthly or annually, your help will power our local reporting for years to come. With enough support, we’ll be able to hire more journalists and produce even more great stories about your community.

But we aren’t there yet. Support us for as low at $1.62 per week, and rest assured you’re doing your part to help inform your community.

- Tyler, Joti, and Grace.