Stand on the dirt road that overlooks the Lytton townsite, and you can imagine the sensory cacophony of a town rebuilding. The sound of hammer on nails; the smell of drying paint and wet tar; the sights of lives starting over.

But you need to imagine it. Because down below, Lytton remains a flattened heap of dirt and concrete, amid which only a handful of workers sifting methodically and patiently through dirt for debris and contaminants, as they have done for the past year. Security workers linger. Traffic is rare.

Seven days after Lytton burned to the ground in 2021, BC Premier John Horgan stood in front of an array of cameras and pledged to rebuild.

More than that, Lytton would be rebuilt as a “community for the future” and become an example of successfully preparing for a warmer climate, Horgan promised.

But 600-plus days into that future, rebuilding remains a goal, not a task. In the face of delays and bureaucracy, some displaced residents have decided not to return, whenever that might be possible. Others have had the choice made for them: on this February morning came news that an elderly resident who dreamed of returning and rebuilding had died, a new Lytton still a concept, rather than a reality.

Today, the village has become another sort of case study.

This is the story about the immense difficulty of rebuilding a tiny, traumatized community, and how BC’s post-disaster gameplan was ill-prepared to pave the way to reconstruct a village in its darkest hour.

This is why Lytton remains, as its new mayor calls it, “a wasteland.”

This story was written based on interviews, previous news coverage, interviews by other media, footage from council meetings, and personal observations from more than a dozen trips to the townsite throughout the last two years.

Journalism like this costs a lot of money to produce. Help us keep producing work like this in the Fraser Valley.

In early March, 2023, the clearing of lots in Lytton continues. 📷 Tyler Olsen

One: The question

“How is the rebuilding coming?”

It’s a question Denise O’Connor hears frequently when she heads out of town and encounters someone who learns that she is from Lytton.

Over and over, O’Connor must break the news: there is no rebuilding.

“They seem surprised,” she says. “They often will ask ‘Why is it taking so long?’”

That was also the question that O’Connor and her former neighbours asked in the days, weeks, and months after Lytton burned to the ground.

And they were given plenty of reasons by local and provincial officials. The ground was contaminated, the legacy of colonization required archeological work, city records were destroyed, and everyone was traumatized. Usually, promises followed the excuses: that the latest obstacle would soon be cleared and building would start relatively soon.

And yet here we are. Clearing the shells of buildings took nearly a year. The only rebuilding of note came in December, with the erection of new power poles. But those poles still have no homes to connect to.

Since the fire, O’Connor said she felt no sense of urgency on the part of those in charge of the process. And as displaced residents watched the government rapidly deploy resources following the atmospheric river, they began to question whether rebuilding their village was really a priority.

“We worry that we’re so small that we don’t matter,” she said. “I don’t know how true it is, but there are definitely those feelings.”

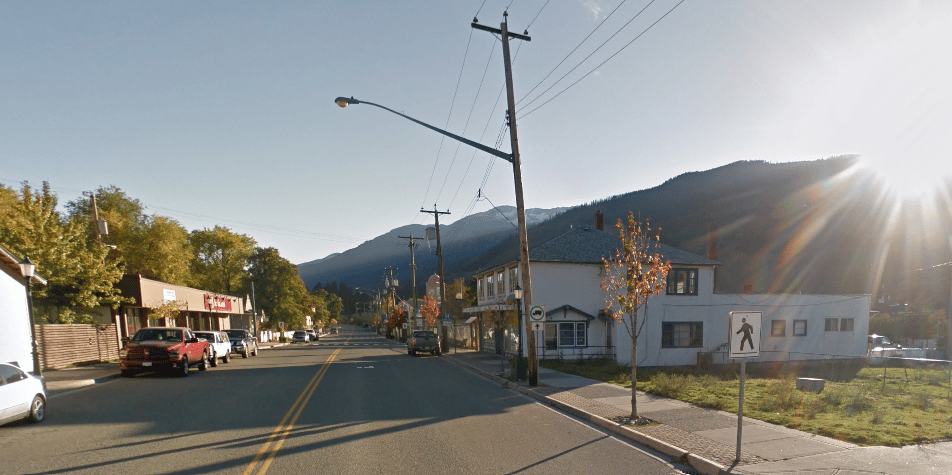

📷 Google Street View

Two: The Village

Lytton is a special place. It has been so for thousands of years. It remains so today. But the things that have made it so special—its history, location, climate, and people—all complicated the rebuilding process.

The village centre—the heart of the fire and of the community—is perched on a small plateau perched above the confluence of two of BC’s largest rivers: the Thompson and the Fraser. Many of its homes and buildings had been around for more than a century, but Lytton’s history was far older than that. Its location had long been recognized by Indigenous people, who had lived both on the village’s tiny plateau and in the surrounding area for thousands of years.

When Europeans arrived, they also recognized the importance of the area as a key transportation corridor. Today, the Trans-Canada Highway and the country’s two main rail lines all pass within just a few hundred metres of themselves—and the village site.

In 2021, only a couple hundred people lived in the Village of Lytton and the compact First Nation reserve immediately north of the downtown core. But the village site was a hub of activity and a commercial centre for the couple thousand people who lived in the wider area. The village had hotels, tourist attractions, a well-stocked grocery store, a bank, a legion, and a range of other amenities. It had a bustling farmer’s market and busy streets, with tourist signage and a rainbow crosswalk. It was, in many ways, an urbanist’s dream, with essentially no sprawl. Almost all the amenities and shops were located in one convenient area.

Many of Lytton’s residents were seniors, who could walk everywhere they might need to go in the village. It wasn’t particularly wealthy. And it wasn’t growing. But it had its niche and it served it well.

📷 Google Street View

📷 Tyler Olsen

Lytton has long been known for its heat. A welcome sign (that still stands today) declared it to be “Canada’s Hot Spot” for good reason. No place in Canada broke the 40 C threshold as frequently as Lytton. While a Saskatchewan town held the Canadian record for the highest temperature ever (45 C), Lytton had hit the 44.4 C mark in 1941, setting (along with a couple other communities) a BC record that would stand for 80 years.

Looking back, the scale of the heat wave BC endured in June of 2021 is still remarkable. And nowhere was hotter than Lytton. When national and provincial heat records fall, they tend to do so incrementally, with advances by decimal places. But on June 27, the temperature reached 47.9 C recorded in Lytton, nearly three full degrees hotter than any temperature previously recorded in Canada. On June 28, Lytton broke its own record. It did so again on June 29, when the mercury nearly hit 50 C.

This reporter briefly stopped in Lytton that day. To step out of one’s car was to venture into a blast furnace. Above town, smoke lingered from a wildfire that crews had miraculously kept at bay. And along the highway on the fringes of town, blackened grass showed where ground and air crews in the area had rapidly snuffed out previous spot-fires before they could cause trouble.

Three: The Fire

June 30 was another scorcher. Streets across British Columbia were quiet as people and workers took refuge inside. Hundreds had already died in the heat wave. In Lytton, the record heat had lost its novelty. The trees and grasses were crisp and dry. The grass and pines swayed as a fierce wind blew north up the canyon. As afternoon marched on and the mercury climbed into the high 40s, a train rolled up the canyon.

The precise cause of the fire is still an open question. It is believed to have some human connection, but that leaves immense room for possible triggers, ranging from a deliberate act to a carelessly discarded cigarette to a spark from a passing vehicle.

Many residents blamed the ongoing train traffic that continued to pass through town.

Trains have been linked to fires in the past, and a couple reported seeing a train on fire 44 kilometres south of Lytton, in Boston Bar. A 2021 Transportation Safety Board report did not find any “definitive connection” between a train that passed through Lytton shortly before the fire ripped through town. But neither did it determine any other cause or conclude definitely that a train did not cause the fire. (With locals continuing to pursue a class action lawsuit against the rail companies, a judge may eventually be asked to decide not whether a train definitely caused the fire, but whether a certain company’s trains were more likely than not to be to blame.)

Whatever sparked it, the fire that would burn Lytton down started in the worst possible place, given the wind.

The fire was first reported at 4:38pm. It was later confirmed that it began immediately south of town next to the railway tracks in an area officially known as “Hobo Hollow.” From a tiny spark, the gusts created an inferno that pushed it to the north and west. It began so close to town, and moved so quickly in four different routes, that fire crews had no chance to respond. The focus, from the outset, was on saving lives and running. It spread incredibly quick, in some areas as fast as 14 km/h.

By 6pm, the entire village was on fire, with flames leaping from one building to another.

Only a handful of buildings survived. The ambulance station and police department were incinerated. The Lytton Chinese History Museum was razed. Banks, hotels, and the area’s only places to buy groceries all burned to the ground. The fire also killed (a rarity for a BC wildfire) claiming the lives of two seniors who reportedly tried to hide from the flames in a trench.

Residents of Lytton fled in whichever direction they could, awaiting a time they could return and reclaim their town. It would take far longer than anyone would expect.

Journalism like this takes time and resources. Make sure we can continue producing award-winning work by becoming a Current member for less than $2/week.

The Lytton fire spared fewer than a half-dozen buildings, wiping out the village hall and a backup location for the municipality’s records. 📷 Tyler Olsen

Four: The Aftermath

The fire that burned Lytton was also special, though in a spectacularly bad way.

The inferno left the village a mass of wreckage. Concrete and steel needed to be bulldozed and removed. The husks of cars needed to be carted away. Tonnes of contaminated dirt and debris needed to be tested and disposed of.

But all that is par for the course after a wildfire. From Barriere to Kelowna to Grand Forks, floods and fires have ravaged more than a few British Columbia communities over the last two decades and the total number of buildings destroyed in the Lytton fire was not unprecedented.

But Lytton’s rebuilding task would be much larger, in large part because Lytton itself was so much smaller than those other communities.

BC fires typically start outside of a town or city and nip at the community’s fringes. They may take a chunk out of a town or paralyze an entire city, but after the embers cool, life in the majority of a city can begin to return to normal. Residents return to the surviving houses, while those who lost homes can find temporary accommodations in hotels or with friends or families. The grocery stores and offices and police departments fundamental to 21st Century life remain.

And because there are generally more people who survived relatively unscathed than those who were victims of the event, there are neighbours and family members to help out. While those who lost homes may need time to process their loss and put their personal affairs in order, their neighbours can carry the physical and mental load of beginning the rebuilding process.

That is what happened in the Fraser Valley following the 2021 floods. The number of people who needed direct help was larger than the number of people who lost homes in Lytton, but a relatively small portion of the entire region’s population. So those who needed to rebuild their lives could do so, while others who lived on higher ground could focus on the bigger picture of guiding the overall recovery. The process worked more or less as it was designed to, with locals doing the grunt work and provincial and federal governments providing millions in financial support.

Lytton, though, was obliterated. The fire didn’t take a bite out of the village. It ate the whole thing. Its commercial and service core was as hard-hit as its residential area. There were too few homes in the surrounding rural areas to accommodate all those who were displaced. There were no motels or hotels where people could stay. There was nowhere to buy groceries or other essentials. The community was gone.

📷 Tyler Olsen

And the damage was even worse than that.

“The problem with Lytton is the whole village collapsed,” said Ron Mattiussi, an outsider who would be called upon to lead recovery efforts in the town.

The fire didn’t just physically obliterate Lytton’s homes and businesses. It also destroyed Lytton’s bureaucratic and institutional backbone in ways that still endure today.

The flames destroyed the village office and all the physical records stored there. Backups were stored at another location in town that was also destroyed. (One lesson for all towns: don’t keep your only two sets of documents in a place where they may be vulnerable to a single natural disaster.)

Just as damaging was the mental toll. In burning down the homes and the workplace of Lytton’s council and municipal office, the fire exacted a tremendous toll on the precise people whose efforts and expertise would be critical to any speedy rebuild.

The fire levelled not only dozens of homes, but the commercial backbone of the village and surrounding area. 📷 Tyler Olsen

The stress following the fire would have been almost unimaginable. Residents had fled among highways flanked by fire. They drove from their homes and, in rearview mirrors and glances at the sky, saw their community recast as a black tower of smoke. Lytton was suddenly on everybody’s tongue, and its residents—be they business owners, retirees, municipal workers or part-time politicians—faced an unending list of personal post-fire worries, and tasks, and obligations.

But BC’s post-disaster gameplan required, by its very nature, many of those same residents to lead the rebuild.

“We can’t underestimate the fact that the people trying to fix [Lytton] were also people who experienced the trauma, and the council had experienced the trauma,” Mattiussi said in November of 2021

The task in front of those people would be immense. The village had only a few workers, and none had been hired for their expertise in helping a tiny municipality rebuild. Lytton no longer had a village office, bylaws, or residents. Its council was living elsewhere. The list of tasks was endless. The expertise was not.

Five: The hired gun

Mattiussi had run Kelowna’s emergency operations centre during its devastating 2003 fire and worked for more than a decade as the city’s general manager. Over the ensuing 20 years, he built a reputation as the guy to call when a city needs help after a major disaster. (Mattiussi assisted both in Fort McMurray and Grand Forks following disasters in those two communities.)

The day after the Lytton fire, Mattiussi’s phone rang. On the other end of the line were provincial officials looking for advice on what the heck should be done next. He provided his thoughts, then watched from a distance as frustration mounted over the following months.

Many of Lytton’s village staff had quit their jobs, and residents were growing frustrated by a lack of on-the-ground action.

“When will the rebuild actually happen?” resident Edith Loring-Kuhanga asked in October of 2021. “Will our seniors actually be able to see their homes rebuilt? Will they still be alive to see that? Every day lost is a day stolen from them.”

Finally, after months of little progress on the ground and amid increased resident complaints, Mattiussi was asked to provide more hands-on guidance and help the village’s council set a path toward recovery. Eventually, after the village’s overwhelmed chief administrative officer quit, Mattiussi was asked to step in to head the municipality’s bureaucracy.

After leaving Kelowna, Mattiussi had regularly worked as an interim CAO in other BC municipalities that needed a short-term guiding hand while searching for a replacement for their top bureaucrat. But in Lytton, he found an entirely new challenge: a municipality with essentially no written records, no staff, and a council who were living in Kamloops.

“Sometimes the silliest little things are a lot harder than somebody may think, like getting someone answering the phone,” Mattiussi would tell a reporter soon after starting the job.

Finding permanent staff was an almost impossible job.

“We found it really hard because the problem was so complex to get anybody with experience that could could handle all those components,” he recently told The Current.

Journalism like this costs a lot of money to produce. Help us keep producing work like this in the Fraser Valley.

Six: The Gameplan

BC’s post-disaster process didn’t help much. Nor was it really designed to.

Unlike the United States, where the Federal Emergency Management Agency might step in to take over the recovery of a community, British Columbia’s post-disaster model is much more locally focused.

The provincial and federal governments might provide funding after a disaster, but it’s the local community that generally decides the steps taken to rebuild what was damaged and lost.

“Normally, a recovery would look like: part of Merritt flooded, and then you assign someone to do the rebuild, to go get the grants, and go figure out what they needed to do,” Mattiussi told The Current.

In the wake of the Sumas Prairie flood, for example, the City of Abbotsford set up a bureaucratic apparatus to oversee rebuilding, issue permits, dole out money, and make plans for repairing infrastructure and reducing the likelihood of a future disaster. That system emphasizes local decisionmaking and puts the process largely in the hands of the community affected. In doing so, it derails some of the conflict that the more top-down approach in the United States sometimes creates.

Mattiussi said Canada’s approach is generally effective.

But Lytton’s post-fire experience shows the glaring flaw in a system that hands power to a local municipality and its officials and relies on their expertise. Because in Lytton, the province handed a task to a tiny government that was fundamentally unable to cope with the mountainous task in front of it.

“The model we use [in Canada] actually works,” Mattiussi said. “The problem is …the model is predicated on the other levels of government co-ordinating with and helping the local [government]. But if you don’t have a local government—”

The federal and local governments pledged millions of dollars to the village. They then waited to see how the municipality wanted to spend that money, relying on Lytton officials to take the lead, without seeming to fully comprehend that it was incapable of doing so.

Take the matter of temporary housing for residents.

Early on, temporary housing near Lytton was identified as a key need. But none was ever provided for residents.

The Current asked the province about why no temporary housing was provided for residents. A government communications official wrote back, saying that residents had received temporary housing for more than a year (referring to those provided housing hours away).

As for on-site housing, the government official wrote that Lytton had been provided funding and could have submitted a proposal for interim housing, or asked for “guidance,” but that it did not do so.

The Village of Lytton did discuss the matter. Plans were ongoing already in October 2021, but by the following August, the village, beset by a rotating cast of staff members, many of whom have little experience with such tasks, was still trying to plot a course. No temporary housing has yet been provided.

Shifting timelines also have complicated local decisions. The government spokesperson pointed to a promise of $21 million the province made for such infrastructure improvements. But that promise was made a full year after the fire. By that time, Lytton First Nation residents were preparing to move into temporary homes funded by the federal government. Meanwhile, Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth was promising rebuilding was imminent and would likely begin in a couple months.

Everything has taken longer than expected—and promised—and Lytton’s isolation has increased the pain of waiting.

Following previous fire disasters in western Canada, displaced residents have been urged to be patient. But those residents have largely been able to remain living within their previous communities—and able to count on the continued functioning of their local government. The comprehensive destruction exacted by the Lytton fire, coupled by the remote nature of the village, made it impossible to expect residents to find a semblance of normalcy following the disaster.

Over time, the provincial government tried to add resources. Provincial officials had been the ones to call on Mattiussi to begin with. The government also provided advice and a recovery team to “enable the village to lead its own recovery,” a provincial spokesperson wrote.

And yet for 18 months, on-the-ground work in the village was a relatively rare site. And that left residents wondering how committed the province was to a speedy rebuild.

After the atmospheric rivers hit, BC rapidly deployed resources to re-open the Coquihalla and other highways. Some had predicted the highways would be closed into the spring, but the Coquihalla was re-opened to all traffic in mid-January, barely two months after it had been destroyed.

Locals took notice.

“There’s a joke in our (community) Messenger group that if only we were a highway, we might have seen some movement,” Lytton property owner Jennifer Thoss told CTV in March of that year. “Money is great, but it feels like there’s a lot of people at the helm and it doesn’t translate into action.”

The immediate aftermath of the fire saw outpourings of sorrow and despair. Many pointed the finger, with cause, at a warming planet. It’s well-established that human-caused climate change is resulting in broadly warmer temperatures, more severe heat waves, and more frequent extreme weather events. The scale of the BC heat wave points to a worrying future, with previously unimaginable temperatures priming forests for fire.

The 2021 fire and heat wave suggested that Lytton was particularly vulnerable. So in the immediate aftermath of the blaze, the focus of many outsiders was on how the village might be rebuilt to survive some future calamity.

Just days after the fire, BC’s Premier talked about a rebuilt Lytton becoming a “community of the future.” He said Lytton could serve as a case study that other places facing similar challenges might seek to emulate. There was talk of sidewalks that functioned as solar panels and homes that would be built to withstand fire and net-zero buildings and wind energy.

In the fall of that year, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau addressed the UN Climate Convention and spoke about the destruction of Lytton.

“In Canada, there was a town called Lytton,” Trudeau said. “I say ‘was’ because on June 30, it burned to the ground.”

Scattered across British Columbia in hotel rooms and makeshift accommodations, Lytton residents bristled. The town’s chamber of commerce responded with a blistering email, calling out the Prime Minister for seemingly confining their town to history.

“To hear you, Prime Minister, refer to our town in the past tense in your speech… breaks our hearts,” they wrote. “Let us assure you, the town of Lytton still exists. It exists in the hearts and minds of every resident and every business. Writing us off, as you did by referring to us in the past tense, reflects exactly how we have been treated.”

Even nearly two years later, neither Trudeau, nor Horgan, nor his successor has set foot in Lytton.

As politicians talked, as a petition lingered on desks awaiting a response, as emails awaited replies, and soil samples sat waiting for processing, the husk of Lytton sat under a glowing 2021 sky, and its residents lingered in hotels and family spare bedrooms and Lower Mainland campsites.

Journalism like this costs a lot of money to produce. Help us keep producing work like this in the Fraser Valley.

📷 Tyler Olsen

Seven: The Dirt

The largest recovery challenges involved the dirt and soot left behind the fire.

Immediately following the fire, before any work could be done on the site, provincial rules required soil testing and reports on environmental contamination. Little on-the-ground work was needed, but it took months for an initial report to be completed. When that report was finished, it wasn’t provided to residents for several weeks, heightening the tension and uncertainty. During all that time, no one could enter the disaster zone.

The delays immediately after the fire came back to haunt the town when, just as some progress was being made, record storms barrelled through BC, destroyed highways, and cut the village site off from most of the province—including its displaced residents and potential remediation workers—for more than a month. Epic snow storms followed, burying the townsite.

Meanwhile, it became increasingly clear that dealing with the past would be a large job, both physically and bureaucratically. When settlers originally built houses on the land, they did so at a site that had served as an Indigenous gathering place for thousands of years. The remnants of those gatherings still could be found beneath the wreckage of the fire, and recovering those pieces of history was deemed to be necessary before they could be built over again.

That required carefully sifting through each property—and, seemingly, a bunch of paperwork.

Each property would normally need its own permit. Eventually, the province made the entire village a single archeology zone. The province painted the move as a noble deed: it said the move would benefit residents because they wouldn’t have to each get costly permits, even though the cost of which would have been imposed by that same government.

Eventually, the job of overseeing all the work was too much even for the one man the province had hoped might be able to fix Lytton’s problems. Mattiussi left his post last year. He told The Current it was “for my own physical health.”

He is now retired.

“I’m always here to help and I still am. If they pick up the phone, they can call, but I just can’t do the job full-time.”

The decision to film an upbeat commercial in Lytton last year was described as ‘baffling’ by the province 📷 ATCO

Eight: The Local Politics

It’s not a mystery why the recovery has stalled.

“Everything that happened is explainable,” Mattiussi said.

But that doesn’t mean a quicker rebuild was impossible.

That much is clear from the different rebuilding paths seen in the Village of Lytton and on Lytton First Nation lands.

The First Nation includes properties and homes that burned immediately north of the village centre. (It also includes land and rural neighbourhoods on the other side of the Thompson River that escaped the bulk of the fire’s wrath.)

But while the municipality’s recovery process has been plagued by red tape and inaction, work on destroyed properties on Lytton First Nation land started quite soon after the fire.

There are several reasons for different rebuilding paths.

A big one is the fact that the village, like other municipalities, is bound by provincial laws, while the First Nation is under federal jurisdiction.

Take that first environmental contamination report, for example. It wasn’t required for Lytton First Nation land, allowing residents to return to their properties and pick through the remnants much earlier than their neighbours. The oversight of necessary archeology work was also inevitably more complicated on village lands where there were simply more stakeholders involved.

The temporary housing situation was another key difference. While village residents have remained scattered and no temporary homes were ever built locally, modular homes were erected on Lytton First Nation land to allow displaced residents to remain in their community.

When asked about the lack of temporary housing, a provincial spokesperson pointed the finger at the village government. Despite having its own governance questions to deal with, Lytton First Nation had applied for and received support to create temporary housing, a provincial spokesperson wrote in an email. The Village of Lytton could have done the same, they said, but did not file the necessary application or ask for help doing so.

Leadership and council decisions played a role; so too did a lack of available land. While the fire burned through the vast majority of village land, large segments of LFN land remained unburned, including one neighbourhood a couple kilometres outside of town. There, more than a dozen trailers were erected on a lot immediately next to the First Nation’s health centre.

The survival of many LFN homes also meant the local leadership and population was not displaced to the same degree as their village neighbours. And vital infrastructure also survived, including that health centre and a gas station and convenience store. (The First Nation welcomed remaining Lytton residents for community celebrations, and used their equipment to plow village roads.)

In the village, the delays caused anguish and strife.

Often after a natural disaster hits a community, that city or town’s local politicians become fixtures in the media and around their communities. They help rally spirits and plead for money and resources from senior levels of government. But almost immediately, a disconnect began to form between Lytton residents and its local leaders, even though those leaders had lost their own homes in the fire.

The rift emerged barely a month after the fire. In one of council’s first post-fire moves—and amid talk from provincial politicians about how Lytton could be a “model community” built to withstand climate change—the local politicians proposed a strict new building bylaw. The new rules set out stringent energy efficiency and fire-mitigation measures. Some of the rules referenced items like barbecues and wood-burning stoves that residents highly valued.

Experts said adopting such rules would set the tone for municipalities in vulnerable areas across Canada. But residents worried that doing so would make rebuilding their homes more expensive and less hospitable. Wood-burning stoves, residents said, are necessary in the winter when the power goes out. Residents said they weren’t consulted, and that the rules felt imposed.

When the village finally did adopt a new building bylaw, the new rules it set out would be more moderate than first suggested. But a damaging gap between residents and their elected leaders had already been established.

Before the fire, the city’s mayor and council did not start with a strong mandate. In 2018, there had been no election: only one person ran for the mayor’s chair, and there were only four candidates for the village’s four council seats. The job was relatively thankless and hardly lucrative—the mayor made only $7,500 for a year’s work. And none expected to have to rebuild Lytton from scratch at the same time they needed to rebuild their own lives. Before the fire, one councillor had already resigned. Another would quit post-fire after making controversial comments on social media.

Frustrated residents visibly wrestled with how much to blame or expect from their local leaders. Council, meanwhile, bristled at the criticism they received. Nevertheless, a pattern quickly emerged after the fire.

Residents would complain to the media about the pace of rebuilding. In response, then-mayor Jan Polderman would try to explain the delays, point to complicating factors, and promised work was underway to expedite rebuilding. BC’s public safety minister Mike Farnworth would echo that message when pressed on the slow pace of the recovery.

Polderman and his council rarely publicly criticized the province and expressed gratitude for whatever help was offered.

Nothing summed up the problems more than an infamous commercial filmed in Lytton last summer. Council gave the greenlight to ATCO, a company that provides modular trailers, to film an uplifting commercial shot in the town. The commercial suggested rebirth. But residents had been told they couldn’t walk the streets without wearing protective gear.

"It's kind of like a slap in the face to see these little kids walking around," resident Micha Kingston told CBC.

Polderman suggested there were only a handful of critics and stressed that ATCO had paid the village $50,000 in return. Before the fire, that money would have been a huge sum for the tiny village. But the argument that Lytton needed money wasn’t well received, given the provincial and federal governments had already promised tens of millions of dollars. It was such a mis-step that even provincial Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth condemned the decision.

“It is not something that I would have done,” he said. “Council makes these decisions... I find it quite mind-boggling.”

ATCO apologized and pledged more than $100,000 to the village.

Meanwhile, the province continued to promise that rebuilding was around the corner.

In March of 2022, Farnworth blamed the lack of advancement on the weather and the closure of highways during the atmospheric river, but said the province was “taking action to speed up the process.”

Three months later, on the anniversary of the fire and with much of the archeological and contaminant paperwork seemingly taken care of, Farnworth said he expected rebuilding work to start within a couple of months and that residents would be returning to their homes within the next year.

Eight (B): The provincial response

Asked about the rebuilding, a provincial spokesperson refused to answer why a BC premier had not visited the town.

Asked specifics about rebuilding, a provincial spokesperson cited the millions of funding provided to the village for a variety of post-fire activities. They also said the province was increasing the number of permanent staff in its “Disaster Financial Assistance and Community Recovery programs to better support communities and individuals impacted by disasters.”

And finally, they said changes have been made to provide more up-front cash to “help accelerate local recovery planning.”

Most of the changes, however, appear to still require a functioning municipality in order for them to improve responses. It remains unclear if BC has the tools in place to react more quickly the next time a disaster wipes out an entire municipality.

Asked if there was any plans for a report or analysis of the response, a spokesperson wrote: “After action review is part of the emergency management cycle following an event. In the case of Lytton, EMCR is continually reviewing our activities to seek improvements that best support recovery efforts.”

Local journalism matters.

Become a Current member today and help stories like this come to life for less than $1.91 per week.

Tricia Thorpe and her husband decided to start rebuilding their energy-efficient house near Lytton immediately after the fire, relying on community help and not bothering with permitting. 📷 Tyler Olsen

Nine: The Insurgents

A couple months after the fire, in October of 2021, I drove up a gravel road etched into a fire-ravaged-canyon to visit Tricia Thorpe on her property just northeast of Lytton.

Years earlier, Thorpe and her husband had retired to a small mountainside acreage with a spectacular view just outside the village limits. The home and several farm buildings had burned as the fire swept north and debris still littered their property that fall.

But when I visited that October, Thorpe and her husband were already erecting the fireproof walls for what would become their net-zero home.

The pair had encountered their own bureaucratic obstacles: she had heard, at one point, a local official suggest her home was still standing. Their response had been to proceed anyway without any permits. They took a just-watch-me approach, while building a new home with fireproof and energy-efficient material.

“What reasonable person is going to look at us and go ‘No, no, you can’t?’” she said.

The pair received help from volunteers and donations from community members. And by the following May, Thorpe moved into her new home.

Her story was shared widely, and even used by a governmental agency as an inspiring example for how new homes can be rebuilt in a fire safe way.

“You can do it on your own,” she said in a video posted on the website of British Columbia FireSmart, a group of government agencies. “Building is not my thing and we figured it out.”

But as Thorpe and her husband took the initiative, she watched as her neighbours and friends who lived in the village were barred from returning to their homes and rebuilding. And some began to re-evaluate their life plans.

Lytton wasn’t a wealthy town. Its median income was 30% lower than the BC average and many homes were a century old—you could get one in 2020 for $105,000. Few had assessed values exceeding that. And uncertainty about insurance has been a constant theme since the fire.

“I have two friends [in the village] who have already bought elsewhere,” Thorpe told me back in 2021. “That’s sad.”

Ten: The Votes

While their leaders played it nice with senior levels of governments, Lytton residents were far more vocal in calling out the lack of rebuilding.

The most prominent were Thorpe, O’Connor, Thoss, and Loring-Kuhanga, the administrator of the nearby (and still-standing) Stein Valley Nlakapamux School.

On social media and local Facebook pages the foursome wrote forcefully about the need for more community consultation and a quicker process. They spoke up in council meetings, and weren’t shy about repeating their complaints to reporters looking to keep British Columbians abreast of how rebuilding Lytton was going (or not going).

Although they said they weren’t opposed to the efforts to promote energy efficiency and fire safety, they stressed that delays came with real costs.

October’s election showed that their neighbours agreed.

The incumbent Lytton political leaders declined to run for re-election.

“I think when you have a fire, council loses some credibility,” Polderman had told the Vancouver Sun. “I lost credibility.”

Thoss, Thorpe, Loring-Kuhanga and O’Connor all stood for elected positions during last fall, the latter two vying for the mayor’s chair. Thoss sought a Lytton council seat, while Thorpe ran to be the director in her regional district area.

Only Loring-Kuhanga didn’t win a spot, losing out to O’Connor in a good-natured race. In Lytton, turnout from the scattered community approached a remarkable 70%, and all three mayoral candidates criticized the length of time the rebuild was taking. (A third candidate named Willie Nelson also won a handful of votes.)

Still, some bitterness lingered. After the election, the outgoing council held one final meeting. Members passed a new building bylaw for the village, over the objections of the incoming council, four members of which also attended the meeting.

In her closing remarks, outgoing councillor Lilliane Graine condemned her successors.

“I find it somewhat laughable that they’re thanking us for the good job that we did when they’re the people who have been harassing and attacking this council for 15 months,” she said. “I would like to say that you should be ashamed of your behaviour, but I doubt you will be.”

But earlier in the year, Polderman had predicted that time will cool tensions.

“The anger directed my way will subside, and I hope a new mayor can move forward,” he told the Sun.

📷 Tyler Olen

Eleven: The New Mayor

Four months after the election, O’Connor stood with me on a dirt road that overlooked the townsite. Lytton’s new mayor pointed out the location of her home, now gone, and the path of the fire through a village she had lived in most of her life.

O’Connor grew up in the village, leaving only to go to university. She returned a short time after graduation and got a job teaching. She would eventually become the principal of the elementary school, retiring only in 2018. Like many in such small towns, she wore a variety of other volunteer hats and served on various community committees and the town’s chamber of commerce.

Unlike many of her former neighbours, O’Connor had been able to return to Lytton relatively quickly after the fire. Her old childhood home was still in the family and survived the fire. When renters moved out in the fall of 2021, O’Connor moved in. Returning to Lytton gave her a first-hand look at the recovery, or lackthereof. It allowed her to start managing a local resiliency centre to provide help to other residents. And it also gave her an inside look at meetings between various government ministries and local officials.

Leading up to the election, residents had asked her to run, knowing she was both vocal and, crucially, actually present in the town.

“One day, I just woke up and went ‘Yep, I can do it,’” she said.

O’Connor was joined on council by four other women, only one of whom had served in the previous term. She said the transition from critic to mayor has been eye-opening.

“We all thought ‘We’re just going to be able to get in there and start getting things moving and, well, that’s not the case.’”

The new council members have had to learn just how to run a council meeting (and a village that only kind of exists). They’ve also had to try to unpack each of the many obstacles to progress and rebuilding.

O’Connor is still adamant that the start of a rebuild could have taken place much quicker. But the emotions and anger that followed the blaze have simmered with time.

“People ask me now: ‘Who do you blame? And I don’t really know. Like—” she shrugged.

In some aspects, the challenges remain one of getting the people to do the job. When the new council took over, the village didn’t have a working recovery manager. That position may be filled soon, but the village also now needs to replace its chief financial officer, who left after finally recreating the municipality's financial records from scratch.

O’Connor has never talked to Trudeau or now Premier David Eby, but she did recently give the province’s new emergency management minister, Bowinn Ma, a tour of the townsite.

That, she said, was important, and she said she was grateful for the interest.

“They need to see what we’re talking about,” she said. “They need to be here.”

Contrary to Farnworth’s predictions last year, residents will not be returning to their homes by June.

O’Connor knew about the bureaucratic obstacles, but even she has been taken aback by the governmental complexity behind the rebuild.

I asked her if there had been any surprises from seeing the process from the inside.

She gave a chuckle, saying “there’s been so much.” But her tone quickly became more serious. “The slowness that everything takes. I knew it, but I didn’t know it, if that makes sense.”

O’Connor will be told by a government worker that good news is coming, only to learn that the progress comes in the form of the formal approval of funding that had been promised a year ago. Then there is the question of what might lurk in archeology reports that are expected soon.

Still O’Connor (like her predecessors) does see progress coming.

“I think building will start this year,” she said. “To what extent? I don’t know…. There’s some who go ‘We don’t know if we want to come back. And there are others saying ‘We have insurance, we’re going to rebuild.’”

Correction: This story originally said the region’s only grocery store burned down. Lytton actually had two places to buy groceries. They were both destroyed.

Times are tough, and we know not everyone is in a position to pay for news. We’re in part reader-funded, and we rely on the ongoing generosity of those who can afford it.

This vital support means tens of thousands of locals in the Fraser Valley, and beyond, can continue getting local news, and in-depth, award-winning reporting.

Whether you give monthly or annually, your funding is vital in powering our local reporting for years to come.

Support us for less than $1.91 per week, and rest assured you’re making a big impact in our community.

Join us, and become a Fraser Valley Insider member today.

Find this story interesting? Check out our three-part look from last year at how small Fraser Valley communities struggled following the 2021 atmospheric rivers: