- Fraser Valley Current

- Posts

- Trauma and the tracks: First Nations wrestle with the legacy of rail deaths and land theft

Trauma and the tracks: First Nations wrestle with the legacy of rail deaths and land theft

Indigenous people face re-traumatization from trains that move through their communities and struggle to get 'direct engagement' with railway companies to solve the issue

Squiala Chief David Jimmie stands by the CN Rail tracks that bisect his reserve. Jimmie has lost several family members to train-related incidents in his lifetime. 📷 Grace Kennedy

This story first appeared in the June 26, 2025 edition of the Fraser Valley Current newsletter. Subscribe for free to get Fraser Valley news in your email every weekday morning.

This story deals with suicide, train-related fatalities, and Indigenous trauma. If you are experiencing thoughts of suicide, call 988 to access BC’s Suicide Crisis Helpline. If you are Indigenous, you can contact the BC-wide Indigenous crisis line toll-free at 1-800-588-8717.

The cemetery at the Squiala First Nation is small and enclosed, with headstones placed neatly around its grounds. Across the road is a playground, and when the air is quiet, you can hear children playing.

A marker in the centre of the cemetery bears Squiala’s name; gravel paths lead from the monument to the edges of the graveyard. During funerals, families walk down those paths to remember their loved one. A crowd gathers, the grave is covered, and silence descends for a moment. Unless a train rattles by.

On an overcast February day, Squiala Chief David Jimmie stood beside the cemetery gate and considered the tracks that lay beyond. “Our cemetery’s right here,” he said. “While you're conducting your service and going through ceremony, you've got a loud train that comes through—it's just another aspect of that re-traumatization for some people.”

Since the 1980s, more than 120 people have died on the Fraser Valley’s train tracks. Data from the Transportation Safety Board of Canada doesn’t identify how many were Indigenous, but historic newspaper accounts and anecdotes show that dozens of Indigenous people have been killed by trains in recent decades, both in accidents and through suicide.

And deaths aren’t the only way rail companies have negatively impacted Indigenous communities in the Fraser Valley. Land theft, infrastructure costs, and a lack of co-operation with local First Nations has created issues for the Indigenous people who live next to CN and CPKC tracks.

This story deals with suicide, train-related fatalities, and Indigenous trauma. If you are experiencing thoughts of suicide, call 988 to access BC’s Suicide Crisis Helpline. If you are Indigenous, you can contact the BC-wide Indigenous crisis line toll-free at 1-800-588-8717.

The Squiala First Nation is small, with only 223 members and even fewer living on-reserve.

“It used to be called Jimmie Reserve,” Jimmie said, explaining that the community was centered around his grandparents and their seven sons. “We’re all related in one way or another.” Squiala has two main reserves, one off Eagle Landing Parkway and another at the base of Chilliwack Mountain, along with several reserves it shares with other First Nations.

For Jimmie, the rail tracks are a reminder of the trauma his people have experienced, and a real ongoing risk to his band members’ health and safety.

The Stó:lō people—including Squiala and two dozen other First Nations—have lived in the Fraser Valley for generations beyond count. The train tracks that cut through their land have been there for a little more than a century. They’ve created challenges throughout that relatively brief existence.

The railway next to Squiala is easily accessible. Blackberries form the main barricade between the tracks and the reserve’s grassy lawn. A private driveway into an empty field crosses over the tracks at the reserve’s eastern edge. (A driver was killed at that crossing in 1993 when a train plowed into a truck hauling woodchips.)

People are often killed by trains at the crossings. Although some of the deaths are accidents, others are likely suicides. A report into a 1992 train fatality near Squiala described a train crew that observed a person moving toward the tracks.

“It became apparent that [the] trespasser was not going to wait for [the] train and was struck,” the report said.

It deemed the incident a suicide, and noted that conductor and engineer had been placed on stress leave.

This tragedy was not unique. Newspaper reports have covered many train-related deaths of Indigenous people, occasionally including gruesome details about the state of the body. Many of those reports noted the deaths appeared to be suicides.

Suicide rates among Indigenous people are three times higher than among non-Indigenous people. Intergenerational trauma stemming from colonization, abuse, the relocation of communities, the forced separation of families, and the loss of culture and language has affected First Nations communities across Canada for decades. That trauma contributes to and aggravates ongoing struggles related to substance use, mental illness, and poverty.

Some intergenerational trauma comes from the effects of legislation created to deliberately remove Indigenous people from their land, and disconnect nations from their territories. The Indian Act, which determined who was Indigenous, where they could live, and what they could do, also dictated what happened to the meager amounts of land allocated to bands.

The Indian Act dictated that the reserve land where band members lived was owned by the Crown—not the First Nation and its residents. The Act also allowed railways to expropriate land from reserves without compensation.

(First Nation governments in British Columbia could not actually purchase land in their own name until last year; most needed to use corporations or societies to hold the land even though the First Nations Land Management Act in 1999 gave some First Nations more power over their own land.)

When the Canadian Northern Railway began considering where to lay its track in the early 1900s, it consulted white homeowners, but not local Indigenous people and communities. (Canadian Northern Railway eventually became the Canadian National Railway.)

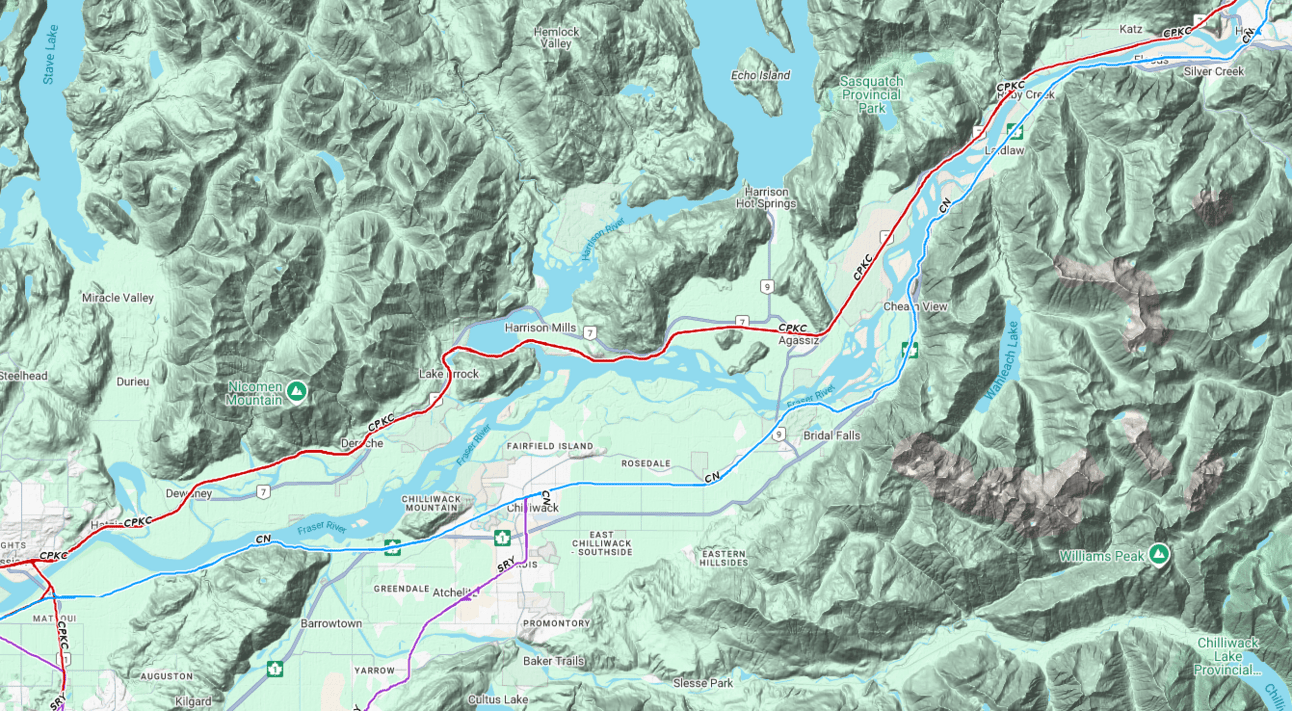

Between Sumas Mountain and Hope, the Canadian Northern Railway took land from at least six different reserves: Squiala, Cheam, Popkum, Peters, Shxw’ow’hamel, and one Leq’á:mel cemetery on Sumas Mountain. Frequently, those expropriations split the reserves and made it more difficult for First Nations to shape unified communities.

Squiala’s reserve layout makes that abundantly clear. Squiala’s core residential neighbourhood is located on a section of reserve that is constrained by Ashwell Road and the railway. It has around two dozen houses, as well as the band office, a daycare, and an education centre. To the south, the band chose to focus on economic development by establishing the Eagle Landing shopping centre and Home Depot.

Jimmie said the band is trying to place as many homes as possible on the available lots in the neighbourhood, but that there is only so much space to work with. Although the band is also building a subdivision on its Chilliwack Mountain reserve, a lack of easy access to amenities makes it hard for some families to live there.

“It makes it tough,” Jimmie said about the railway dividing Squiala’s land. “You’re building your sense of community around the main area. Eventually, you outgrow it.”

Squiala is pursuing a claim against the railway related to the loss of its on-reserve land. Jimmie said he said he couldn’t reveal details, but that it could take more than a decade to see a resolution.

The loss of land is just one impact on Squiala and other First Nations. The railroads continue to pose a safety hazard that compounds generational trauma among members, Jimmie said. He said the private railway companies have shown a lack of support and consideration for the communities impacted by their trains.

The lack of communication is not new. Interactions between railways and local governments are largely dictated by regulations, but Jimmie said little has been proactively done to include First Nations in decisions.

“They send their annual communication plan or their thoughts around how they can mitigate what they can, but we never really have any direct engagement,” he said.

At a national level, CN Rail’s entire Indigenous Advisory Council quit in 2023, saying the company “missed the mark” on reconciliation. The advisory council had been formed two years prior and was chaired by the late Murray Sinclair, the former chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It was intended to provide advice and foster relationships between nations and the railway company.

"We've decided that our utility to CN is no longer worth the effort that we're putting out and that they need to decide what to do about that,” Sinclair told CBC when the council resigned. He said CN’s proposed reconciliation action plan was a source of disagreement between the company and the council.

The railway company has not, at least publicly, created an alternative committee.

Would better communication reduce the number of deaths that take place on tracks next to Indigenous reserves? Maybe, Jimmie said. Warning signals, new overpasses, and stronger barriers on tracks could also help reduce the number of accidental deaths, although Jimmie warned that those were not a silver bullet—and are often unattainable when local governments are the ones funding the new infrastructure.

Because train tracks usually predate city roads, municipalities are generally responsible for maintaining or upgrading railway crossings. Chilliwack has long considered building a rail overpass at Young Road, and had a $14.5 million structure listed in its five-year capital plan. (The actual cost would likely be much higher.) But in an interview last fall, Chilliwack Mayor Ken Popove questioned whether an overpass would be able to stop suicides on the tracks. Jimmie is more supportive of infrastructure changes on the tracks, but also noted that the problem is a complicated one.

“We could put up a bridge or more signs, and [those] I think are all good and helpful, but there’s a larger systemic issue around some of the social hardships or intergenerational trauma,” Jimmie said.

In Jimmie’s lifetime, at least seven Squiala residents have died on the tracks, including a group of cousins who took their own lives around the same time as one another.

“That was devastating in the community,” he said. “Everyone chips in and everyone helps whenever there’s a loss … So everyone has been directly impacted at one point or another.”

The trauma continues to linger long even after the event is over. Trains passing by a funeral can remind mourners of the way their loved one passed. And even something as simple as whistles can also re-traumatize community members.

The crossing at Yale Road, just a kilometre and a half away from Squiala, is the deadliest spot on the Fraser Valley’s tracks, with many people dying at or near the crossing. 📸 Grace Kennedy

Last June, following the death of a pedestrian near Eagle Landing, Transport Canada ordered that trains needed to slow down and sound their whistles at crossings when travelling through Chilliwack—and past the many reserves in the area. Many Chilliwack residents complained to the mayor about the noise. But for some Squiala residents, that horn was far more than just an irritant.

“You’ve got mothers, brothers, uncles, aunties, cousins that have all gone through losses … and so that horn can be quite triggering,” Jimmie said. “You’re healing it more often, so families are being triggered more often, and it’s something that no one came and talked to us about.”

More engagement between railway companies and First Nations would be one step towards a solution, Jimmie said. He suggested the company should undertake new safety studies, to examine the causes of deaths and learn from communities about what they would like to see change. He noted that the now privately-held companies continue to amass wealth from the trains that run through Indigenous land—and occasionally kill Indigenous people.

“I’d love for them to hear from some of the families directly impacted,” he said. “It’s a different story when you talk to a mother or father who’s lost their child, rather than just reading about it.”

More programs for Indigenous people living on- and off-reserve to support youth, keep families together, and provide counselling would also help, he said.

Some of that work is ongoing or beginning, although there is still a long way to go. In the meantime, the tracks are still there, sitting quietly beside reserves across Canada until a train clatters along.

“I don’t really have an answer, a solution,” Jimmie admitted, walking down the road that divides CN rails tracks from Squiala’s band office.

At the CN Rail crossing on Eagle Landing Parkway, just a few metres away from where Jimmie was walking, an orange display of flowers was nestled in amongst the rocks. The small bouquet was just barely visible to passing cars: a glimpse of colour in the rearview mirror.

They represented yet another person who had lost their lives on the tracks, and the family who survived them—a family who would remember their fate every time they passed a railway crossing, or heard a train whistle blow.

If you have thoughts of suicide there is help available for you. Everyone can call any of the following numbers to receive support in times of crisis.

Fraser Health Crisis Line: 604-951-8855 or 1-877-820-7444

310-Mental Health: 310-6789 (For 24/7 mental health support, information, and resources)

Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868 (For 24/7 anonymous support for young people up to the age of 20, including support over text—just text CONNECT to 686868.)

Indigenous people experiencing thoughts of suicide or other crises can call any of the following numbers for Indigenous-focused help.

Hope for Wellness Helpline: 1-855-3310 (For 24/7 crisis support and intervention; an online chat is available)

Kuu-Us Crisis Line: 1-800-588-8717 (For a 24/7 BC-wide Indigenous support line)

The Sto:lo Service Agency also has supports available for Indigenous people living in Sto:lo territory. For youth suicide resources, email [email protected]. For the mental health team, email [email protected] or call 604-824-5136.

Reply