British Columbia’s population might be growing, but fewer and fewer new residents are arriving directly from the womb.

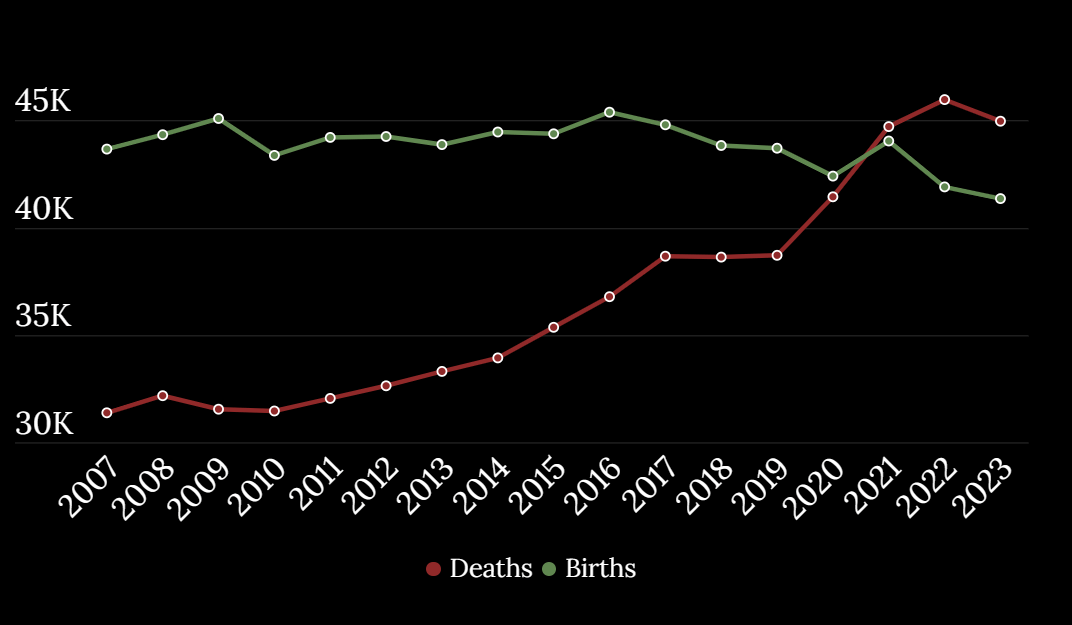

Two years ago, The Current broke the news that, for the first time in history, the number of deaths in the province had exceeded the number of births. That grisly gap held firm in 2023, data confirms, as the number of babies born plunged even further. But there has also been a change, with the number of deaths dropping for the first time in years.

Today, we revisit a story from two years ago in which we revealed that births had exceeded deaths in BC for the first time in modern history.

Tomorrow, we’ll look at birth and death rates across the Fraser Valley.

The gap

In 2022, British Columbia recorded around 600 more deaths than births, finally passing a threshold it had been creeping towards for more than a decade.

The difference between births and deaths has fluctuated over BC’s histories. In the 1950s, and then again in the early ’80s and ’90s, the province registered tens of thousands more births deaths. Even just 15 years ago, in 2009, around 13,500 more babies were born than people died. But ever since then, the gap between births and deaths has been shrinking, largely due to BC’s aging population. The arrival of the opioid crisis and the COVID pandemic have also pushed death rates sharply higher in recent years.

Combine those trends with a sagging birth rate, and you get more dead bodies than newborn babies by the end of 2021.

A little more than two years later, the gap has widened even further.

Note: These figures are drawn from public records collected and released by BC’s Vital Statistics Agency. You can find them here. The locations of the babies reflect the home address of the mothers—not the hospital at which the baby was born. Similarly, the location of deaths is based on the home address of the individual who died—not the specific location of their final breath.

The babies

You’ve heard of a baby bump. Meet the baby slump.

Last year, just 41,324 babies were born, according to BC’s Vital Statistics agency. That’s the fewest live births in nearly two decades, and about 600 fewer babies than the previous year. BC’s birth figures have been declining on an annual basis since 2016, with the exception of 2021, when the province recorded a significant spike in births, possibly linked to the COVID pandemic. (The 44,073 births that year were about 1,600 more than 2020, and more than 2,000 more than 2022.)

Birth rates are heavily influenced by the age of the population—as well as cultural and economic factors affecting people who might consider having children.

Statistics Canada surveys reveal many young people are putting off or reconsidering having kids because of the cost of housing. And while Canada has welcomed a large number of immigrants in recent years—including young people in their twenties and thirties—it’s likely those newcomers will take some time to become settled enough to start families.

So for the moment, BC is undergoing a baby bust. It may not be permanent—these things tend to come and go as some generations have more babies than others, and as those babies grow up and have their own children. It’s also not uniform. The birth slump manifests itself differently depending on location and community. The rapidly growing Fraser Valley, for instance, saw local mothers give birth to around 100 more babies in 2023 than five years earlier. We’ll have more on the local breakdown of babies in a follow-up story.

The deaths

Babies and births are not inevitable. The flip side of the coin very much is.

A growing population almost inevitably leads to more deaths as its participants continually fail to achieve immortality. Even so, BC’s death rate says important things about the state of the province and its people.

In 2022, British Columbia registered 45,998 deaths. Stoked by both the still-ongoing COVID pandemic, the opioid crisis, and an aging population, that figure was 19% higher than the death total from just three years prior. It also represented the culmination of years of increases as baby boomers, as they moved into their seventh and eight decades.

Last year, though, there was a change. For the first time in more than a decade, significantly fewer people died in British Columbia than the previous year. The 2023 death toll was 1,150 people shy of the 2022 figure, representing a 2.5% plunge in the number of final departures.

Early indications show that decline won’t continue. Last year’s reduction in deaths may have marked a return toward the status quo after several years of totals goosed by the deadly impact of COVID. And so far, more deaths were recorded in January and February than the same time last year.

Common sense too suggests we won’t continually see fewer deaths. While the number of births can be heavily influenced by personal choices, deaths are inevitably more impacted by diseases, health crises, and mostly by how old the general population is. And BC doesn’t just have more folks eligible for generous seniors discounts, it has increasingly huge numbers of people entering their late 80s.

In 2020, BC’s population was about 4 million. Of those, about 57,000 were over the age of 85. (These figures were assembled by The Current using the province’s population projector application.)

By last year, BC’s population had grown by a third to about 5.5 million people. But its population of people over the age of 85 had more than doubled—and the number of people older than 90 had almost tripled. BC now has around 120,000 people who are older than 85. That doesn’t just translate to more deaths, eventually. It is also a big reason why the province’s health care system is increasingly unable to keep up with demand and why it’s so hard to find a doctor.

By 2030, the province expects to be home to 164,000 people older than 85. And another 201,415 people will be between the ages of 80 to 84.

History suggests BC’s birth totals will eventually stop declining and head back up. There’s no sign the number of people dying will do the opposite.