The Boundary Lake wildfire broke out near Fort St. John earlier this month. 📷 BC Wildfire Service

This story was first published in 2023. It explains why many colder Canadian landscapes—including those in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba—are more susceptible to spring fires than BC’s warmer Southern Interior.

As Northern British Columbia and Alberta burn, southern BC has largely been spared flames so far.

It might seem counterintuitive that fires start earlier in the west’s colder climates, but it’s actually fairly common. That’s because geography and biology conspire to make southern BC relatively fire resistant in spring, even as places further north begin to burn.

But just because the south has been spared this spring, doesn’t mean the hot dry weather won’t have an impact this summer.

The fuel

The boreal forest of Northeast BC and Northern Alberta is dominated by spruce and jack pine conifers, along with deciduous aspens.

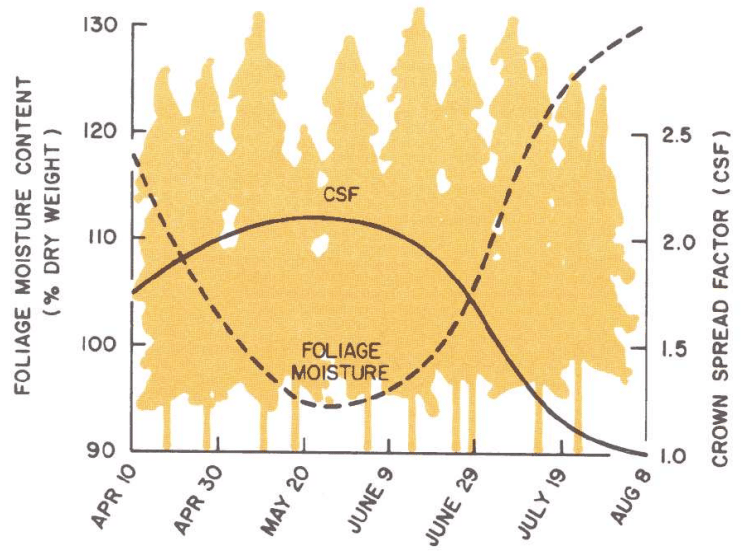

Early in the spring after the snow melts, conifers go through their annual “spring dip”—a short period during which their needles become extremely dry, and susceptible to fire. (The “dip” refers to their moisture content) By late spring, a tree will begin producing new, greener, less-fire-prone needles, but until that happens, the tree is a matchstick waiting for a spark.

At the same time that the pines are drying out, the aspens and other deciduous plants in the boreal haven’t yet fully awoken from the winter. A lack of leaves and greenery leaves the forest dangerously exposed.

“You have direct sunlight reaching a forest full of dead leaves and needles and branches,” Chilliwack-based wildfire expert Robert Gray said.

Any spark can trigger a blaze in these dry, brushy areas. Winds push those flames along the ground, beneath the barren aspen canopy. When it reaches a pine tree and its ultra-dry needles, a fire can spring into a forest’s canopy. And from there, propelled by warm spring winds, it’s off to the races.

“You have the perfect conditions for pretty fast-moving fires,” Gray said.

Combine that with April being one of the driest times of the year, and this is why the most devastating recent fires in the northern boreal forest—the Fort McMurray and Slave Lake blazes, along with those this year—all occurred in May.

Southern BC—at least the Interior—can also be very dry in spring. But paradoxically, it is usually less prone to cataclysmic May fires.

BC’s central and southern forests have many things in common with the boreal forest (the jack pine is similar to Southern BC’s uber-common lodgepole pine). But there are also important differences.

Aspen are rarer and generally settle in relatively wet valley bottoms. BC controversially manages its timber supply for harvesting reasons, reducing the amount of aspens in its sprawling harvestable areas. (This has consequences lter in the year.) And the south has a more-diverse range of ecosystems, ranging from the broad grasslands near Kamloops to cedar-dominated forests of the south coast, to the densely forested mountains of the Kootenays.

Some of those—especially the aspen, which burn much more easily before they get their leaves—play a factor in its different fire seasons. But, perhaps most importantly, southern BC has hills and mountains.

The mountains

Southern BC’s forests also go through their own “spring dip” period each year. Its pine trees also lose moisture and become much drier and its underbrush also is exposed to the sun’s rays.

But while the province’s forests do become much more susceptible to fire, fire rarely threatens southern communities in the spring months.

Of 84 blazes designated “wildfires of note” in BC in 2021 and 2022, just one began before June.

When fires started to ravage the southern interior in June of 2021, that was actually a relatively early beginning to the season fed by an unprecedented heat wave. BC’s largest fires tend to occur in late July or August after prolonged periods of summer heat.

A lower proportion of deciduous aspen allowing the sun to dry out the underbrush in spring is one possible reason for the relative lack of spring fires. But possibly the biggest factor is BC’s mountains and hills. (Of course, vegetation and geography are not entirely separate from one another; a region’s vegetation is related to its geography.)

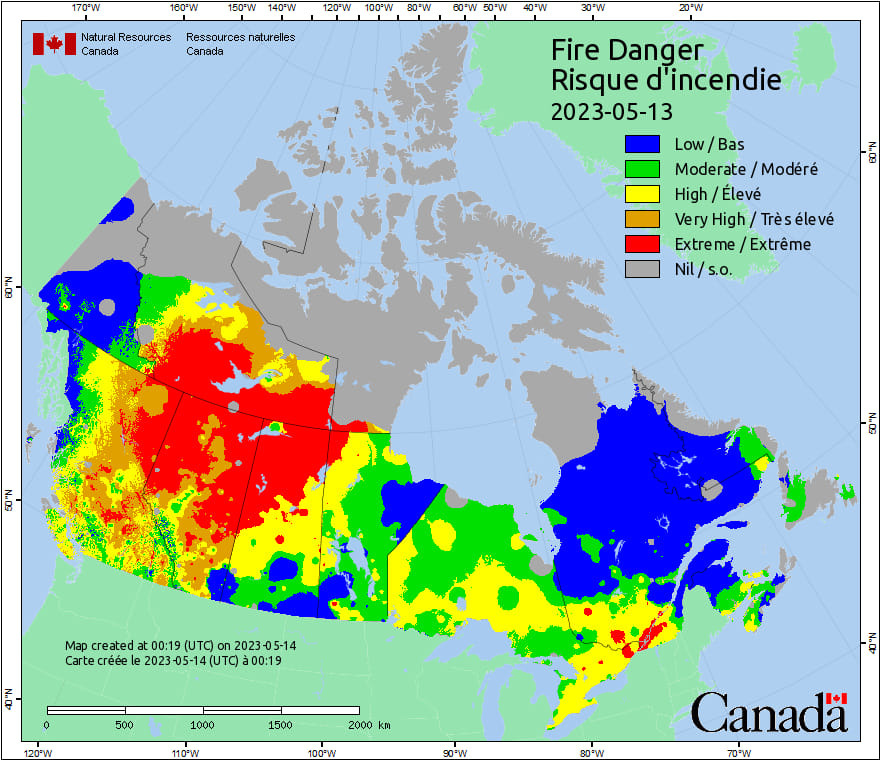

In Alberta and Northeast BC, the flat landscape means that the spring dip hits the entire landscape at the same time. So when flames engulf one bone-dry pine, it’s likely surrounded by huge swaths of similarly fire-prone vegetation.

Flat topography leaves huge expanses of wilderness susceptible to fire at the same time. 📷 BC Wildfire Service/YouTube

“As soon as it’s dry, it’s dry everywhere,” Gray said. The flat terrain also encourages high winds that can push flames quickly across long distances.

That’s not the case in the mountainous south, where spring fires can’t go far before finding themselves in less welcoming terrain.

In BC, a plant’s moisture content at any one time can depend on its elevation, the slope of the hill it sits on, and the direction that hill is facing. A shrub on a south-facing side of a tiny gully may bloom significantly earlier than those on the opposite bank. Snow that disappeared from the base of a mountain may linger for months at its top. And wind has to battle its way through a maze of valleys and hills that shield its plants.

That inevitably reduces just how fast fires spread. Forester and ex-firefighter Thomas Martin has found that the bulk of land burned each year comes during just a handful of extreme days—often when wind is particularly severe.

Although fire broke out on a mountainside near Squamish earlier this month, its growth has been limited. Five days after discovery it had grown to just 38 hectares, a fraction of the size of fires in northern BC—or those commonly seen in summer in BC. 📷 BC Wildfire Service

The result is that at any one point in Southern BC, only a small proportion of the province’s trees are in the “spring dip” phase that is most conducive to the creation of a mammoth May wildfire like those seen in the province’s north.

Experts like Gray, who use controlled burning to reduce fuels in forests can use that to their advantage.

“When we do burning in the springtime, we rely on the fact that when it goes around a corner [of a hill], it’s going to die as soon as it hits this moisture barrier where it’s shaded in the north aspect.”

The fire danger map for May 13 illustrates this well. While the northern boreal forests include large swaths with the same fire danger, southern British Columbia is much less uniform. Here, a forest’s susceptibility to fire is very dependent on its elevation and hills. Pockets of extreme risk are surrounded by less dry conditions, limiting the potential for disaster.

Fire inevitably seeks to travel uphill. But as a blaze works its way up a BC hillside in spring, it will head back in time, season-wise. The temperature can drop by a degree for each 100 metres of elevation gain. In BC’s steep mountains, that can leave a valley in the grips of spring within shouting distance of ground still partially covered by snow.

When that snow eventually melts, much of the water flows downhill—often unseen below the ground’s surface—into otherwise drier and warmer valley-bottoms. That moisture contributes to the growth of plants and trees, while making them less susceptible to fire during the spring run-off season.

That doesn’t mean BC is fire-proof of course, or that a spring wildfire can’t damage homes or harm people. It just means the province rarely sees the spring fires that displace thousands and burn dozens of homes.

Caution is still required when in the forest. And the advantage only lasts for so long. Because even if large fires haven’t yet broken out across Southern BC this May, the current heat wave could be setting the province up for disaster later this year.

What’s to come

Just because Southern BC’s snowpacks and hills usually allow the region to avoid pre-summer fire calamities doesn’t mean hot, dry springs don’t pose a major danger.

Although the moisture content in conifer trees tends to rebound in mid-spring (depending on elevation and proximity to the sun), they soon again begin drying out.

BC’s most-damaging fires have historically occurred in late July and through August, after forests at all elevations and on all slopes have spent months drying out. Those natural moisture fire breaks disappear and southern BC becomes one of the world’s most fire-prone places.

But climate change is both making those traditional fire seasons worse, and starting them earlier. Earlier springs, with drier weather and warmer temperatures trigger both earlier and more severe summer fire seasons. As 2021 showed, that can have consequences both early on—see the June fire that burned down Lytton—and later in the season as the entire province becomes a tinderbox. It also can cause dangerous wildfires in places that have historically avoided such disasters like the Fraser Valley.

Recent years have seen fires near Harrison Hot Springs and Hope prompt evacuations. There are also increasing fire risks in wildfire interface areas in Mission, Chilliwack, and Abbotsford.

Over the last decade, the amount of summer rain falling in the Fraser Valley dropped dramatically. Temperatures are also rising at a significant pace, conspiring to dry out forests at a more rapid rate. The arrival of 35 C heat in May only adds to the threat.

“If we lose the snow quicker in the future, our fire season is going to lengthen because larger portions of the landscape have available fuels,” Gray said.

And the current hot spell is a major worry, he said.

As snow disappears from higher elevations, and moisture evaporates everywhere, the varied fire danger becomes more uniform—and much more dangerous.

The current heat wave has “got everybody on pins and needles,” Gray said.

The rest of May is expected to be dry. If significant rain doesn’t follow, “it’s going to be a very, very difficult fire season.”

If you read and appreciate our stories, we need you to become a paying member to help us keep producing great journalism.

We’re in part reader-funded, and we rely on the ongoing generosity of those who can afford it to help us to produce unparalleled local journalism for the Fraser Valley.

Our readers' support means tens of thousands of locals in the Fraser Valley can continue getting local news, and in-depth, award-winning reporting. We can't do it without you. Whether you give monthly or annually, your help will power our local reporting for years to come. With enough support, we’ll be able to hire more journalists and produce even more great stories about your community.

But we aren’t there yet. Support us for as low at $1.62 per week, and rest assured you’re doing your part to help inform your community.